Item: The Paper Mill Playhouse, one of the leading regional theaters in the country, $3 million in debt, threatens to close its doors unless it receives an 11th-hour transfusion of funds. Crisis temporarily averted.

Item: The New Jersey Symphony, one of the best orchestras in the nation, also experiencing financial difficulties, considers selling rare and valuable musical instruments to stabilize an anemic endowment.

While stemming from different causes, these developments reveal a disturbing pattern. New Jerseyans are simply not supporting the arts at the level that they should.

As Ronald Reagan, who was certainly in a position to know, reminded us, "The arts show us who we are and what we can be." They provide us with joy as well as with entertainment. They make us think. They furnish us with the necessary respite from the pressures of daily life. They preserve and pass on the best that has come down to us from our forebears and add new creations from our times that will give future generations glimpses into the society in which we lived.

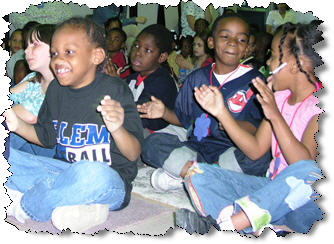

The arts give us all, and especially children, a chance to dream. They are far from frills. It is no exaggeration to say that they are what makes us human.

We hear it said, usually by people who live elsewhere, that with New York City so close, New Jersey does not need a vibrant cultural community. Try telling that to people who have been priced out of Broadway and Lincoln Center by astronomical costs. With New York theater tickets averaging $100 or more, a family of four can expect to pay the better part of $1,000 when one adds to the ticket prices the costs of dinner, parking, gas, tolls and the like. How many New Jerseyans can afford such nights out on a regular basis?

Ask parents whether they would prefer that their children partake in the transformational experiences of live stage performances or waste hours in front of a computer playing mindless — and often violence-ridden — video games. Yet opportunities for them to witness such performances on this side of the Hudson River may be disappearing.

When I was governor, New Jersey arts advocates had a slogan they used to describe their collective goals: "Second to None." By the time I left office, many organizations and individuals who made New Jersey their home were winning national acclaim.

McCarter Theater won a Tony Award. New Brunswick's Crossroads Theater did too — just before financial difficulties forced its temporary closing. Architectural critics were writing about two additions to the Boston-Washington cultural corridor: the expanded Newark Museum and the magnificent New Jersey Performing Arts Center. I could go on.

All of this did not happen by itself. It required investments of talent, energy by the state, by corporations and by individuals and, yes, money.

In my years as governor, the state's investment in the arts reached an all-time high of $23 million. When I recall that the entire state budget then was approximately one third of what it is now (a bit more than $12 billion compared with $33 billion today), I grow dismayed that the state invests as little as it does. This year, the governor has requested an appropriation of $21 million to the state Council of the Arts. His request, if granted, would come up more than $2 million short of the amount 20 years ago.

When one factors in an inflation rate of 3 to 4 percent each ensuing year, the governor's request constitutes a cut in real dollars of more than 30 percent since the '80s. That $23 million in 1988 would be $37 million today. In the same period, the state budget almost tripled.

With tourism being New Jersey's second-largest industry and with cultural and historical attractions ranking high on lists of what visitors expect to see, such cuts are more than shortsighted. They are harmful to the economic health of our state.

Back in the 1980s, the Port of New York and New Jersey released a study that showed that for every dollar that cultural enterprises spent, they attracted an additional $4 into local economies. One need only visit New Brunswick to see how a thriving arts community, backed by a supportive business community and government, can help revitalize a city. The same is true of New Jersey Performing Arts Center in Newark. As sure as dusk follows dawn, cutbacks by the state signal to the private sector that New Jersey does not value what the arts do for us and our children.

Sadly, there are signs that state corporations have gotten this message. After 20 years of meager state investment in one of the few parts of the budget that attract private giving (prisons do not; highways do not; many social services do not), private-sector investment in cultural pursuits is not what it should be. While some of our oldest and most established companies, such as Prudential, Johnson & Johnson, PSE&G and a handful of others, remain generous to arts organizations located near their headquarters, too few of the others, in comparison with what their counterparts are doing elsewhere, are contributing.

The same can be said of well-to-do people. In other locales, ticket holders and subscribers often make annual contributions to cultural enterprises. Too little of that happens here. I cannot count the times that I have walked into a museum or a concert hall in New York and seen high on the list of donors, public-spirited people who live here in New Jersey

People choose to live here and corporations stay here in part because of our rich cultural climate. In this, the 60th year since Jackie Robinson permanently transformed American baseball and even longer since New Jersey's Paul Robeson did the same for the world of theater and opera, it is time that the state, our corporations, and, yes, you and I stepped up to the plate, onto the stage and into the seats.